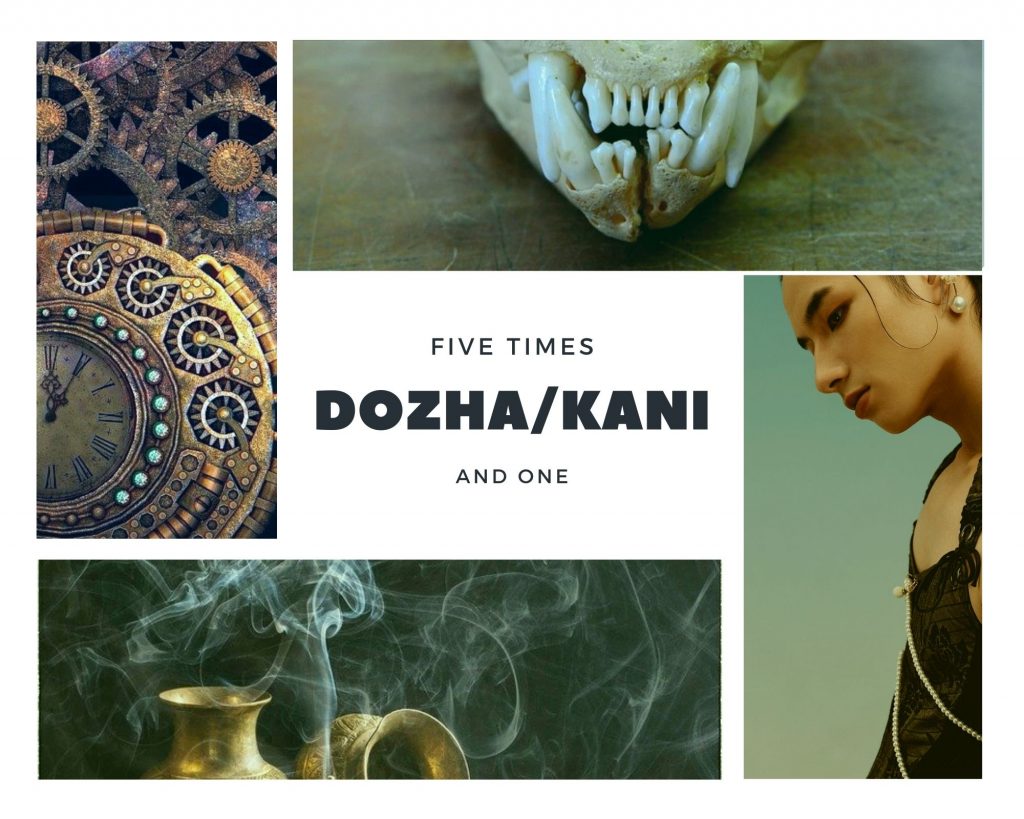

These are two post Thief Mage, Beggar Mage ficlets that show the different sides of the same coin.

WARNING FOR MAJOR SPOILERS, so definitely only read these if you’ve finished the book.

5 Times Dozha Did Not Fall in Love, and One Time He Did.

1

It was not easy being the adopted child of a dragon, chosen for one thing and one thing only. Dozha knew that Sinastrillia did not see his faults and flaws the way humans did. She did not seem to realise that he had only one hand, that his self was as mutable and awkward as a creature forming inside a pupa, somewhere between worm and wasp.

That was something other people noticed.

The first time Dozha left Pal-em-Rasha he took the opportunity to relieve himself of his troublesome virginity. It was better to see pity in a stranger’s face than in the sidelong gaze of someone who knew his name. He could have had anyone in his mother’s Underpalace, but they would have been as wary of him as a snake handler with a cobra. They would have pretended to unsee him.

He let the ice-merchant’s son take him behind the covered wagon, his cheek pressed against the pulsing cold. Dozha breathed words of magic over his skin, and made himself be whatever he thought the man probably wanted. It was quick and raw and disappointing, but there was no fear of losing himself to someone else, or having them follow at his heels hoping for scraps he would not, could not, give.

Strangers were safer.

2

He was only a few months older when Sinastrillia sent him north, so far from the city that his breath turned to ice and he shivered all the time, his fingers aching. He did not understand how anyone could choose to live here.

He hated the high mountains of the Dogs, but they had no temples outside the three great halls of mages, and that was where he had to go. It was the terms of Dozha’s adoption — his singular skills kept secret from the Dogs, from other mages, so that he might become a thief. To be sure, the greatest thief that might ever live, but still a thief.

Dozha was glad to leave the Vaeyene mountains behind as soon as he’d stolen the opal eyes of the dog god Nanak. The opals were a burning weight and he was certain that taking them was an ill done deed, even if it was at his mother’s command. Things were in motion now that his mother had set her board, rolled her bone dice. The game was begun. First move.

The thief-mage stopped at a roadside inn on the journey home, and gave himself softer curves, lowered eyes, whispered promises, and seduced a girl his own age. They taught each other stranger songs in the dark, the soft and kittenish mewls of pleasure. It was an interesting distraction.

3

There were a hundred such distractions over the years, each offering a fluttering moment that was neither completion nor release. Dozha learned to magic himself a prick or a cunt, breasts or none, or both or everything, depending on how bored he was.

This time he’d been hired by Ymat Shoom to deliver a message — a contract that galled, even though it paid well. He was a prince-thief and a mage, not an errand boy. But he was Sinastrillia’s child, and he went, and found things to do, things to take, a pretty girl to fuck even as he stole every damned thing she’d ever owned. It was petty, but he was in a snit.

The man he was to meet was called only Tet; an ascetic, a soldier who had fallen on hard times. What use he was to Shoom, Dozha could not see, but he had a certain lean beauty to him under the traveller’s dust. Dozha, who was used to men and women falling for his trickery, his perfected looks, and ignoring the truth of him, was rattled when the man paid him little attention.

Shoom had said Tet had once been a priest-mage, which probably explained it. His magic was thin, and Dozha supposed that between impotence, prayer, and murder, the man had little time for the dance.

Dozha repaid his lack of interest with a pointless gift, a small snub. A stolen flintpouch for a useless mage.

4

The second time Shoom hired Dozha to meet the ex-priest Tet, it was to rescue him from his own stupidity. Dozha had not expected to feel empathy for the man who had offered himself as a bound sacrifice to Shoom’s webs. If anything, he hated the man for being as trapped as Dozha was. They had both allowed themselves to be caught like mayflies.

But he had not liked to see the man ruined. Naked, hungry, broken. It had taken a great deal of magic to shift both of them into river serpents so that they might escape in the waters of Imal the black, but Dozha had done it anyway, just to see Tet look less stripped. Better to look on him scaled in a new skin than bruised and bloodied.

And for a moment, Dozha had wondered what it might be like if they twined their bodies together in the cold river, knotted coils like serpents mating.

But the moment had passed, and Dozha had delivered the man to Shoom. Had taken his hire coin and left, sloughing away the thoughts of Tet and himself wrapped around each other, scale to scale.

5

Of all the things Dozha had promised, the most sacred was to never reveal the truth of who he was to anyone, and certainly not in a show of mawkish sentiment. He was not ashamed, he told himself. It was that he had no time for the trial of reassuring others through their clumsy understanding, their coming to terms of what he was or was not, what he lacked or didn’t, according to their desires. And he was not willing to unveil himself and end up scoured by well-meant and merciless pity.

Instead he whitewashed his skin, covered his heart with spells and made his face up in mirrors until his reflection was the only truth.

So, when he had allowed Tet to see him, the action had surprised himself as much as it had the other mage. Perhaps it was an act of cruelty, Dozha thought afterward. By being honest with Tet, he’d manoeuvred the mage into a corner, made him taste Dozha’s true skin, feel compelled, perhaps, to offer honesty in return.

Or perhaps Dozha was merely punishing himself for succumbing to emotion. If it was an act of cruelty, then the whip was one he turned on his own back so that he would not be so stupid again.

6

Sinistrallia had promised him a heart.

She had not told him she would take it away as soon as he understood what it was to fall in love.

Dozha stood alone in the ruins of what had once been Pal-em-Rasha’s grand Pistil, and held himself. Around him the woods swayed in the winds, and dark clouds gathered, rolling over the skies on slow-bellies. The rain lashed his face, and Dozha shivered and shivered, and called the true name of the man who had kissed him as he betrayed him.

The world was a vacuum, empty of gods and magic. Empty of the man he called Merithym. Dozha stood in the storm and screamed that name until his throat bled and he too was empty of everything.

He turned to the dark and began to walk.

5 Times Kani Did Not Fall in Love, and One Time She Did.

1

The first time Kani saw herself, it was in a reflection lit by candles. She emerged from another’s skin in soft strokes, brushed in place, the paint whispered deep with words of magic, so that the fiction became reality. Anchored.

She watched the man called Dozha obliterated, and studied his ending with a pitiless detachment. She was more real even though she was a lie constructed for his private amusement.

Kani did not like him, let alone love him. He was a pretender, isolated and fragile in his brittle pride. She would be better, more beautiful.

2

When she finally met the prince she had been made to seduce, Kani found him…interesting. She had not expected that. She knew all the million reasons he was to be played very carefully. She had seen for herself the broken things he left behind him.

But he bowed to her, and swept her hand to his mouth to kiss it, his eyes never leaving her face.

For a moment, suspended and dizzy, Kani felt herself seen.

At the White Prince’s side, his pale shadow also watched her, and Kani smiled at them, and calculated the cost of attraction and what she would earn by whoring herself in increments. How far would she let herself fall to keep the prince’s cold interest only on her.

3

It was a delicate dance, one without an ending. Careful and exact, it had to reveal and offer, then remove and step out of the way. Kani needed to lead the prince in a swirl and chase that was as delicate as it was depraved.

She watched him gut a girl she knew by name, and afterwards, she let him press his hands to her throat, curl his honey tongue against hers. Felt her blood thrum in her ears like the beating of war drums.

Kani wanted to lick his eyes to see if they would taste different, the one icy and sharp as mint, the other like a roasted temple offering, blood and copper. She felt his heat and need, and it made her warm, wet.

In the morning, she stroked the bruises away from her neck, pressing them under her skin, back down into memories.

4

She had paid no attention to the scrambling games that Ymat Shoom played, half aware that in one form or another, she supposed he was her master. But she did not care. She wanted only what she wanted. The prince on his knees before her, his heart in her cupped palms. Yes, there were other things she was meant to be doing, but she enjoyed burying herself in the play, becoming Kani. Becoming the one Lainn wanted because she had not let him have her.

Kani found herself burning like incense when he pressed his thumbs against her carotids and whispered to her the things he would do. Once she was his.

He saw only her. She consumed him.

When her rival piece on the game board finally revealed himself, and turned out to be nothing more than a mage broken by his own power, Kani cut swiftly, mercilessly. She kept him alive, she kept his soul, and that had to be enough. The prince would never have him. Only her.

5

She dreamed of them both. The prince and the mage, the white and the dark, different dances to different songs. War songs and ones without words or meaning.

Sometimes, when Kani let the prince strip her to her waist and run his hands down her, cup the slight curve of her breasts, pinch and nip her, she wondered if the mage would do the same. And between her breasts, the mage’s soul would throb and heat, dig its claws into her skin.

It wasn’t love, because Kani was too much a construct to want love. It would be like expecting a doll made of bone and ash to have a heart. Sometimes, when she could not think who or what she wanted, her dreams would turn strange and she would ride on a giant dog to the hidden bolt hole of the mage, and taunt him with his soul, ask him for his name.

Then he would be hers, and she could see him on his knees before her, his heart in her cupped palms. And against her breastbone she would feel the mage’s need and want, and she would wonder what his black eyes would taste like. Flint and cinders. Burnt out fires.

6

Tet called her by her name.

And Kani was erased. Become Oshaketri. Become Dozha.

The next time Dozha drew Kani’s shadow over himself, it was a costume, a pretty mask. It felt like a skin that he’d outgrown. Kani had been a shape he’d allowed himself to inhabit, because she was the steam valve on his life. He’d played her as an act, then become her, and unbecome her.

He kissed Tet in the cramped attic bed, let himself fill and be filled, and even though he wore Kani’s face, her clockwork arm, her robes, he knew he was done.

Later, when he kissed Lainn in the wide royal bed, he removed the key from the imaginary clockwork woman he had constructed, let her memories die in staccato jerks. There would never be a moment when he would tell Tet the truth of the things he had felt for the man he undressed now.

And if all went as he and Tet had planned, he would never need to.

––